Luang Namtha

My Short Career as a Professional Writer

A couple of months ago I was contacted by an online media specializing in news and info on East Asia. They wanted me to write somthing, AND THEY WERE WILLING TO PAY ME!!!!!!!

Ok, it wasn't much. $50 for around five or six hundred words. The idea is what grabbed me, Pico Iyer, Paul Theroux, and VS Naipaul, Somchai, writers.

They said they'd actually read my stuff! I should have known better. They did tactfully mention that they were prepared to edit for spelling and what not. They were starting a new website and needed someone to write about Laos. That should have been another tell. I, ahem, am hardly a very knowledgeable person about Laos, I just blog about it, one after all hardly needs to know about something to blog about it, the internet is replete with examples of clueless bloviaters.

I responded.

They wanted a few hundred words about Vientiane, like what are "must do" things, and sights to see during a typical one day stay, a short tour guide to the town. Might as well ask me to write about nightlife, I went to a nightclub for one drink fifteen years ago. Transportation, eating, tourist junk. Ok ok I'm a tourist too, and I freely admit it, postcards in pocket, camera, bermuda shorts and flowery shirt, but good grief I'm about the last person to ask where to go in Vientiane, took me ten years before I stopped by Tat Luang, and most people go there first day. I've stayed in a guest house which closed a dozen years ago and a hotel that most say is slightly dingy, otherwise know nothing about lodging. Have never eaten at any of the places mentioned in guides that I'm aware of.

So I wrote it. Not great, not horrid, but typical. You know, about how Vientiane is half about expats NGO workers and the other half is doing the obligatory one day in the capital city to tick the sights on the way to the plane. And I also mentioned the visa runners. If you've been to Vientiane since the changed rules in Thailand or driven past the Thai embassy you have to realize that 200 people a day cycle through Vientiane to renew visas. I did give a general layout of the town, old part near river, little China town, markets, and so on.

Spell checked it, made sure most sentences had a noun and at least the suggestion of a verb and pushed send.

My best line, "Vientiane, a town that rises late, sleeps early, and is lethargic in between". I made that up, really. They kept that line but I'm not sure how much else. They asked for a photo so I sent that one from years ago when I was like 50 years younger and ok looking, with a bolo tie no less, doesn't get much more western than that.

It took a long long time for someone to completely rewrite it. Starts out with something about the "mighty Mekong", ewh!. My mind immediately leaps to never ending dry sand stretching out away from those riverside restaurants. Photos of monks, description of Bhuda park where I've never been. I've done the same for a Chinese Government Tour company only without having someone else's writing as a beginning point. Just crack open a guidebook, read it, then write down all you can remember so it's in your own words of a place you haven't been.

Worst thing is it's posted under my real name. What if an old girlfriend googles my name or the alumni association from that boarding school I've tried to hide from for 35 some odd years reads it! I'm a bad enough writer, I certainly don't need someone adding cliches or describing places I'd never be caught dead in. I didn't save the original so I've no idea how much to blame on some poor fellow who re wrote.

I wrote a short, not snarky at all, email saying we probably weren't meant to be. Never did open a paypall account for them to send money too. I'm keeping my day job.

Up and Down Saw

Click on the arrow lower left (twice) to play the video.

This is the only time I used the video function of my Pana FZ7, the high resolution didn’t work. I wasn’t much into video anyway, still trying to figure out how to take a picture.

These Kammu sawyers were fulfilling a contract to provide wood to the relocated villagers of Ban Nammat Mai. I don’t know what you would call the new village of Nammat Mai, Nammat Mai Mai? I also don’t know why the Akha contracted out the cutting of wood rather than doing it themselves. Certainly an up and down saw doesn’t take that long to learn to use? Notice the rice in the background sown between the burnt trunks of the trees. New slash and burnn due to relocation?

I don’t know what species of wood they were cutting, or how much the contract to cut them was worth especially on a piecework basis. The Kammu guys said they usually cut three or so pieces a day. I also don’t know why they didn’t just chop the wood flat with a knife they way they do in the hills. Notice the peg in the saw cut at the end of the log, probably to keep the saw from binding. How about the language they are speaking, that aint Lao!

One year when my grandfather was a boy he cut his hand badly in the saw mill and so hea nd his brother contracted to cut railroad ties off a wood lot for ten cents a tie. They used a regular axe and a broad axe. The broad axe is used with one hand to cut the logs to flat. I don’t think they got rich on that deal. Seventy five years ago, before workers compensation or Social Security in America. I wonder in 75 years what kind of a world the grandsons of these Kammu guys will live in.

The 22 hour bus to Luang Namtha

Luang Namtha Bus at Northern Bus Station Vientiane

The bus isn’t as bad as the name might suggest. For one thing it never takes 22 hours, they just say that in case. Maybe it used to, I don’t know. I think the whole trip could be done in eighteen or so hours if they eliminated all stops except to the short ones every four hours.

I missed getting seats up front near the driver, so I settled for what looked to be second best, close to the rear door. Good for quick exits for breaks. My wife dropped me off an hour early just to get the good seats but others had the same idea and got the jump on me. The bus did leave pretty much on time even though not full. Sometimes it’s beginning to seam as if Lao busses leave on some sort of schedule, like the one posted in the ticket office. Quite the surprise, I’d been prepared to wait another couple hours for people to show up, and here we were leaving.

The first thing we did after leaving was drive over to the fuel pumps, then we parked up past Dalat Sii Kai for forty minutes. The driver had important things to take care of. You’d think he could have said goodbye to his wife earlier

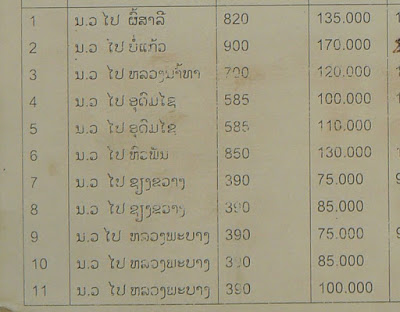

Bus Distances and Price

#1Phongsali

#2 Bokeo (Huay Xai?)

#3 Luang Namtha

#4 and #5 Oudomxia

#6 Hua Phan (Samnuea?)

#7+8 Xiengkuan,

#s 9,10,+11 Luang Prabang

I know you’re probably thinking, why not take the plane. I don’t like the plane. I mean I don’t mind the plane itself, or flying, but I don’t like having to plan my life out two weeks in advance while on vacation, or else fly stand by and have to spend all that time at the airport, and maybe not even go. The bus is simple. Go there, get a ticket, 21 hours later you are in Luang Namtha. I like meeting the Lao people on the busses too. I almost forgot, it’s way cheap. Twelve dollars to go seven hundred kilometres through the mountains.

The bus began to fill up after we got under way. All of those mid sized towns seemed to end up having a couple people. I think we collected five people at that Hmong town of Ha-sip-song. Didn’t even stop at Vang Vien, no English written across the front of the bus. By the time we left Kasi almost all the seats were full.

There were a couple of girls sitting across from me. Kind of chubby and falling out of their too short pants, but friendly, young and silly. For them this was some kind of exciting fun party. The excitement began to wear off by about the thirteen hundredth switch back on the way to Luang Prabang. Everyone was wishing that they could fall all the way to sleep but about the time you would dose off a sharp turn would bump you up against whatever you had been avoiding, to remind you that yes, you are on that bus to Luang Namtha.

I don’t have the route to Luang Prabang memorized yet. There is still a valley that you drive down into towards the latter part of the day only to realize that you still have another mountain to go over. Soon it was dark and the dry season fires on the sides of the mountains were pretty. It seemed like the swathes of open ground were huge, hundreds of acres, the whole sides of mountains. I think the timber industry gave the hill tribe folks a head start on the trees of Luang Prabang. I’ve never seen that kind of a burning pattern for regular slash and burn agriculture.

The southern bus station in Luang Prabang was another food stop, and we all piled out to eat at the bus station restaurants. I opted for a very common barbequed chicken with a side of steamed greens and sticky rice. (Ping Gai, Soup Pak, Kow Nee Ow, and jeao makpet to spice it up) A middle aged Hmong guy from the bus joined me. He was headed only to Pak Mong. A lot of the people weren’t headed to Luang Namtha but rather to points along the way.

Some Chinese people came in the café also, I knew from the clothes but also the proprietress of the restaurant started using sign language and saying, “Shur Fan, Shur Fan”. (Eat rice, eat rice). A couple of the Chinese followed her back to the wok where she stir fried them some rice and they pointed to ingredients they wanted put in. I’d bet a million bucks they also went back to make sure she didn’t put in any plah dek or fish sauce. I had to laugh. Here the Chinese were getting the same food as western tourists. I guess the general rule of thumb at restaurants is, when in doubt, serve them fried rice.

I got back on the bus early, just in time to save my seat from being stolen. The Chinese have different rules of bus etiquette than the Lao. You snooze, you lose. They were well aware of the Lao rules too, they just had a hard time bringing themselves to comply. In China if you behaved like the Lao, you would end up without food, or a place to sleep. It’s the land of sharp elbows. I heard some Chinese guys discussing whether to take a seat, they didn’t want to because there were some half full water bottles left in the pocket behind the seats. It’s hard to not sit down just because someone might be sitting there. Generally the Lao will tell each other who is sitting where, but the Chinese don’t speak Lao, and the Lao didn’t speak Chinese.

I translated as best I could. I never was any good at Mandarin. Immediately I found my voice getting louder and my body language more expressive, as the R’s became richer and the G’s more guttural. I like Mandarin as it’s spoken in China. None of that hissing snake sound of Taiwan for me. The most fun part is calling everyone comrade. I’ve had Chinese people tell me they don’t use that word anymore, and that it’s a word from the old days. I think it’s funny as all get out. China and Laos are both comradely socialist societies moving towards capitalism with a Marxist Leninist approach. Right?

A Lao lady was trying to save the two chubby girls seats for them. Of course the Chinese lady who wanted the seats didn’t appreciate my explanation at all. Much better not to understand. When the people who had been at the restaurant got back on the bus, there were lots of loud voices and gestures, but no truly bad feelings. The Lao were familiar enough with the Chinese to realize that the loud voices are a cultural thing, and the Chinese for their part understood the unwritten bus rules in Laos, and did give up any previously occupied seats. I sized up the scene, and pulled the smallest Chinese guy of the bunch down into the empty seat beside me, he didn’t smoke either. Better him than that chain smoking, spitting fellow with the big shoulders.

Many of the Chinese had trooped into the restaurant as a group. I assumed somehow they were family. Now I began to understand that the two skinny pale young guys who spoke Lao had all the tickets and identity papers. They were the leaders. The others were being brought to various places in China, or at least across the border, probably for a set fee including transportation. Five or six of the Chinese ended up on the plastic chairs mid aisle. That’s how it goes, last on get the worst seats.

One of the young guys made the fellow sitting next to me move so he could sit there.

There was also an argument over the tickets. The price of tickets is set. Seems to be non negotiable and known by all. I’ve never been charged a “falang price” for a bus. The Chinese had paid through Oudomxai I think and they were headed almost to Luang Namtha. They were jumping off at the road to Boten and the border. The busses are privately owned, usually by the driver and his family. The extra fair for all of the Chinese added up to quite a bit of money, maybe ten dollars or more. First the bus kid came back on his usual rounds to check tickets and write tickets to those without. He got nowhere. After consulting with the driver he came back and told them they had to pay. Nothing Doing.

Ten o’clock turned into twelve and the Hmong guy got off. Sometime long after midnight another bus guy came back to talk about the fare with the Chinese. Discussing it were not only the two skinny kids who spoke Lao, but also an older fellow with a very thick neck, the muscle. The whole shouting match arms with arms a flinging was happening about three inches from my face. The bus guy didn’t seem too intimidated, all concerned knew that rural Laos is the wrong place to get in a punch up with a bus guy. You might end up with something bad happening. They paid.

Later still, around three I guess, all the Chinese woke up from their slumber seemingly refreshed and excited to be nearing the place to jump on a pick up truck and head for the border. People broke out snacks and started choking down cigarettes. You’ve got to hand it to the Chinese. Fun for them is taking all night bus rides and then standing around shivering at a remote mountain border waiting for sunrise.

The little guy who had first sat next to me was headed for Shanghai. He had days and days more of this to go. Third class all the way. There is some kind of Chinese expression about bitter soup. I don’t remember how it goes. Something about how you give the Chinese hard times and they manage to make soup out of the deal. Good travelers, I don’t think the tourist label quite fits.

The road to Zhongdien, and Tibet, Yunnan January 1994

The bus rolled into the Luang Namtha station just after five in the morning. Amazing how many people were asleep outside the market on the ground. Families, dogs, vegetables. I waited for someone to wake up at Zuela’s.

Into the Nam Ha Protected Area

Above is the village swing at Ban Nammat Mai, or Nammat New town.

The following is about my trek into the Nam Ha Protected Area with Green Discovery in Luang Namtha.

The village swing is in an abandoned village. All the villages on the trek had been vacated by the Akha. The people had moved to the road, they came back only to hunt and gather forest products. Despite the hill tribes having moved out, I still learned a lot on this trek about the Akha, and the animals and plants that live and grow in the forests of the Namha Protected Area. I probably learned more overall on this short trek than I had on any other. I have many different reasons for wanting to go on treks.

I learned such simple things as that when the name of a village is followed by Gow it means old town, followed by Mai it means new town. Easy to know, but until someone tells you, you are missing out. All hill tribe towns seem to be either Mai, Gow, or if without the designation they have been in their present location for so long people have forgotten about the old town. Hill tribes move. If you know the name of the town it gives you some indication of how long it has been since a move.

I had a very patient and wise guide who would calmly teach me as much as I could absorb. At every break I would jot down things in my notebook. At night and in the morning I would write more. I lost my notebook but remembered many things. This blog entry is partly an attempt to write them down before I forget them. Any and all wrong facts I’m going to blame on the lost notebook, I get sick of prefacing every sentence with the qualifier, “as I remember”.

Ket

Ket, I learned from the other guides when I returned, is a hill tribe person himself. Half Lanten and half Thai Dam. His demeanour wasn’t the ever smiling face of the Lao lowlander. That was ok with me. I never felt the need to make small talk, if I had a question I was free to ask, if he saw or noticed something that he thought would interest me he would speak. His knowledge was thorough and he would give of it freely always qualifying how sure he was of something. When he knew something he would make no comment, when he only believed something to be so, he would mention it. When his knowledge of something wasn’t comprehensive he would mention that also.

The trek cost me a little under a hundred and fifty dollars for three days. I’m not sure of the cost but I am sure it was an insignificant amount. I thought the cost amazingly small for what I was getting, but then I value a walk in the woods with such a naturalist to be invaluable. I signed up for an open trek, meaning if other people signed up they were free to join and the price would also drop. To get an exclusive trek with no joiners would have cost me maybe double. I like having other westerners to talk with, and discuss what we see, and for company, but I always learn more with just a guide. There are many things that a guide doesn’t have to explain to me and I get to focus on things I don’t know.

Colouring the atmosphere of the pre trek arrangements and indeed the whole trek was the abduction eighteen days before of Pawn the manager of the Luang Namtha Green Discovery Branch office and the owner of the Boat Landing Eco Lodge. Someone initially tried to burn his house down while he was in it, and then four men abducted him on his way to an appointment with the police. No one seems to know anything and it is worse than useless for me, an outsider to make baseless speculation. He hasn’t returned to this day. He leaves a wife and as I remember two children. I’m sure all of the guides as well as the American co-founder of the boat landing were missing him very much. They seemed a close knit crew.

Pawn

My trek was the first one since the closing of the office. While making the arrangements for the trek the people in the office were very friendly and informative. Trekking guides are by nature an optimistic and adaptable bunch. I admired their ability to keep a good attitude despite the mixed feelings they must all have been experiencing.

We left in a small pick up to be dropped off at the village of Donexay on the road to Muang Sing. Our local guides were Khamu though the village was mixed Akha and Khamu. The village had moved out of the mountains six years ago. Part of the arrangements with the local villages is that there will always be local guides as well as the senior guide on all treks. It provides some income to the village and hopefully provides an opportunity for locals to learn a trade. Being a trekking guide is a relatively lucrative job, and there is no training or education better than doing it. Another advantage to having two guides on every trek is for safety.

Besides the normal food provisions we also needed to re supply the special trekking huts that had been built for Green Discovery. When all the treks had stopped the villagers had removed everything from the huts. To re-supply two local guides were hired and they carried bedding, cooking utensils and food up to the hut. Ket has three boys about the same age as our two local guides and he seemed very familiar with ordering them around during the trek. I can only imagine how American teenagers would take to being told how to cook, fetch water, clean, gather firewood and so on.

+2-9-2007+10-24-27+AM.JPG)

Guy Ban (local guide) from Donexay

For the first part of the day I concentrated on learning some of the trees and putting one foot in front of the other. I kept hearing the same base name for different species of what I assumed to be the same genus. It took me a while but eventually I recognised oak. Ket called it Mai Goh. Oak is a common genus all around the world. I had a hard time identifying it because the leaves looked somewhat like the live oaks in the southern United States, and unlike the red, white, and scrub oaks that I am used to in the East and Intermountain West. Ket showed me which acorns were edible, and which ones need to be soaked for a few days and the acids leached out. Some acorns were the size of peas and others the size of plums.

Another tree that I was happy to learn about was the strangler fig. I’ve seen them all over and knew they must be something, but I never knew what. The fig grows up the tree as a vine eventually growing more and more trunks and engulfing the host tree, at which time it is strong and thick enough to be self supporting. You often see these seemingly hollow trees with many trunks interwoven to form a single tree.

Strangler Fig

Along the top of a ridge in the afternoon I came across some cat scat, in plain English cat poop. I’m not sure what kind of cat it was, larger than a house cat but not by much. Not much further on we saw another scat that looked like cat but wasn’t as digested. Ket said an animal like a cat, but not a cat. I assume civet. Seeing my interest Ket moved another scat over with a stick causing it to break apart. Finding so much in one place isn’t as unusual as it might seem. Animals use scat to mark territory. The latest poop was filled with hair, and much less processed, looked like coyote, I asked dog? And Ket smiled, “wild dog”.

Then Ket got interested and moved some old half falling apart hairs around with his foot, “tiger” he said. I was of course sceptical and said so. “Look” he said, “dog eat deer, tiger eat pig, look how long the hair.” He was right of course, bearing in mind that for Kep tiger also means leopard. I had noticed the deer hair in the dog scat, looking just like the deer hair that coyotes digest. Two species of deer in Laos are small and a small dog could easily pull one down. The wild pigs are another thing altogether. They are very tough and smart. Any dog that tried to eat one of them might well be dinner himself. The pig bristle was obvious after it was pointed out to me. Of course everything is easy if someone tells you.

Cat Scat

After that Kep started show me lots of things. When some hunters had gone down into the brush to get the civet they had shot from the tree with flashlights, Kep showed me the discarded batteries, and broken bushes where they had gone down the hill. Three guys at least.

I’ve followed people and animals in the woods before. More than a few times. It’s not so hard after a little bit. People have been tracking for ever, and it’s not as difficult as in the movies. It’s all there, just a matter of knowing what you are looking at. Scuffed leaves and ground don’t just happen. Someone or something makes them. I’d never before walked with someone like Ket.

He often would just point and say a word assuming I would get the rest. Wild pig rooting for bugs or roots or something. Feathers from when someone had gotten a bird. I had no idea on the bamboo rats. Never seen that before. The hill tribe people would find the hole and simply dig it out with those short tools that look kind of like a hoe. You could see the trench where they had followed the tunnel back to the rat. Ket said the rats are vicious when you get them unearthed like that. After that Kep would point out every rat hole, even the place the rat had dug down to, and eaten, the roots of the bamboo causing it to yellow out. The stalks came out of the ground looking like they had been cut.

On the second day we came across a fire where someone had cooked up a porcupine and bird. I asked the kid from the village if he’d ever eaten porcupine. When he answered yes I asked him if it was true they had a lot of fat. Big smiles and a yes. I have heard they are tasty all by themselves. When my grandfather was a kid people used to still eat that kind of food. Kep scraped the discarded needles off the trail with a stick. Didn’t want anyone getting one in the foot. Flip flops aren’t much protection against porcupine needles. The quills themselves were shorter, flatter and softer than in the US.

The trees and the forest were, as promised, old growth. I’ve mostly been walking in old uncut forests for a few months now and it seems like the normal way of things. Even where there are villages the amount of cut jungle for rice and farming seems so small. You walk all day through big trees and perhaps a half hour is through rice fields. That section of the Namha does have unusually large trees.

One of my biggest objectives in going trekking with Green Discovery was to see how they handled the tourist, hill tribe, interaction. An owner of a large tour company had given them a glowing recommendation. The trek I went on was more orientated towards forest, all hill tribes were gone. There was another trek I could have taken, that had a couple of trekkers signed up, and I could have saved some money by going. The other trek was only for two days and when pressed the guides in the office said that yes, my trek covered a lot more high ground, and especially old growth forest. Oh well, another day.

I did notice some practices that are built into every trek that I think are an effort to make the experience a good one for both parties. As I said before both villages received some income from our “guy ban” or local guide. Five dollars per guide, per day, actually. Very good money. Twice the wages for a labourer in Vientiane. Green Discovery has a local guide on every trek. I’d only seen them elsewhere when the guide didn’t know where he was going, Green Discovery had them all the time as a standard way of operating. The extra guide has another advantage of safety in case of accident, injury or any other unforeseen circumstances. The local guide is a skilled knowledgeable woodsman in his own right.

Tree

Besides the extra guide there is a handicraft from each tribe included with the trek. Bracelets or a sewn bag, or spoon made of bamboo, that kind of thing. The idea is that there is an exchange, we aren’t just giving money to the mountain people but receiving and being given a physical thing of value in return. I don’t wear bracelets or use wooden spoons, I kept the bag made of cloth scraps and use it to wrap some silver I have. Thanks Khamu kids. With the cost of the licence for entering the Nam Ha Protected Area are costs to maintain it’s upkeep. The cost of the trek includes money to maintain and build more houses like the ones I stayed in.

The hut I stayed in the first night wasn’t in a village. The hut on the second night used to be in a village but the town is now abandoned. First about staying in villages. Where you stay makes a difference. I’ve stayed at the headman’s house and I’ve stayed at another tribe members house and in Thailand and now Laos, I’ve stayed at special houses constructed just for the trekkers. Kep says these kinds of things follow a natural progression.

I thought about that and I got it. The first trekkers stay at the most honoured house. The village has seldom had visitors before from the outside world. By the third of fourth trek maybe some of the magic starts to fade. Foreigners in groups can only understand each other. They are loud and talk and laugh a lot. They get drunk. The chief has other important things to do.

The four or five dollars per tourist the family earns in food and lodging isn’t worth it to the chief. He passes the job off to someone else. They make the money for a while then they too tire. Or maybe they up the price and get sour. I look at it from my own perspective. If I brought a couple or eight foreigners in to sleep in our living room how would my wife like it. Even if there was a lot of money involved. I wouldn’t do it twice.

Foreigners eat first. It’s just the way it is. They eat meat and good food in large quantities. It’s true they give money, but at the end of the day there is one less chicken, or two less kilos of pork to feed the people of the village. The children are hungry. It creates tension in the house if the hungry children are waiting for the foreigners to finish eating. Better to have a separate house to stay in and prepare food without anyone having to wait.

All of the guides of Green Discovery went over to Thailand and took a trek with the tourism authority there, as a way to educate themselves. Thailand has had twenty five years to figure things out. The issues are the same, the hill tribes are the same, and the guides in Chang Mai often even speak Thai Neua. If hill tribes can realize a significant enough income from tourism, and if tourism can be done in such a way that tourists are looked upon with favour, then hill tribe trekking can continue indefinitely. Tourism could even help the inevitable transformation of hill tribe peoples by being a source of income.

Modern Akha Goh in Phongsali

Staying in a house built specifically for trekkers creates a comfortable space for trekkers and leaves a space for the hill tribes people also. If they want to meet and interact they can do so in the more neutral area of the village outside the house. If a tourist makes friends with a villager the villager is always free to invite them into their house. There is plenty of community and family life to observe in the public spaces of a village, without actually staying in a house. A separate house also gives guides a place to cook food. Cooking for a bunch of hungry people using only an open fire and a flashlight can be work. Also guides need to boil water enough for drinking the next day.

Both of the green discovery houses I stayed in had flush toilets of the squat and scoop water variety, a luxury I’ve never seen before but a lot more hygienic than pooping on the ground for the pigs to eat. They are also suitable for taking a scoop shower. They also serve as an example of hygiene for the village. Infant mortality is still high in the villages.

Besides all that, the distance to the first village was too great for a typical trek. Foreigners simply can’t walk that far in a day. We are used to driving around and typing on keyboards. Even people who exercise regularly don’t do it by walking in the mountains all day every day. Exercise is one of the reasons I go on treks, but a I don’t want the walk to preclude all the other activities I’m interested in.

Lunch was from the Boat Landing guest house. It was sticky rice, jeao macpet (hot chilie pepper jeao) and jeune kai, that Lao style egg omelette. The jeao was great, made from those large green chillies, I could eat huge gobs of it without burning, had a great flavour. The jeune kai I would have liked better with at least a little MSG.

We arrived at our hut for the night with plenty of daylight to spare. We had walked without long breaks but taking lots of time to talk about plants and animals. The hut was actually two huts with a picnic table between and two bathrooms out back.. I took a bath in the creek. Very cold, we were up high. Dinner that night was barbequed pork, sticky rice, green beans and of course gaeng jute, the thin soup with vegetables. I noticed the soup had plenty of my favourite flavour enhancer, actually quite a bit. I made sure to try to get our youngest guide to eat as much as he could. He was only ten or so years old. He was shy but after a little prodding he would dig in. We had much more food than the four of us could possibly finish.

+2-10-2007+6-52-54+AM.JPG)

Barbequed Pork, (Ping Moo)

Things were quiet around the fire, I went to sleep early. Lying in bed listening to the animal sounds I thought of how different it was from sleeping in the village. So many sounds it was almost loud. We all slept cold that night, not enough blankets. Towards morning I remembered my reflective ground cloth, I pulled it over me and slept through until sunrise.

The next morning Ket asked me if I had heard the barking deer, so that’s what that was. Ket also showed me all the scratch marks on the tree we were sitting under. The tree is called mai wan because of it’s sweet leaves. Some large squirrel or something had been regularly climbing it to eat the leaves. When I asked Ket about the bird traps in bushes baited with live grasshoppers, he asked me if I had ever seen that other trap, and through hand motions he made me understand he was talking about the deadfall trap. Also he showed me the red flowers of some tree that is a harbinger of the hot season. To spend ten minuets with Ket is to have ten things pointed out to you. Where I see a bunch of green trees he sees, scores of animals and plants.

Mai Wan

Before long, on the second day, we came to a slight trail leading to the top of the ridge. Old Town Nammat, or Nammat Gow. Both Ket and I walked up the hill to call our wives. Another thing these hill tribe people know, exactly where there is cell phone coverage.

Trail to Nammat Gow

I’m not sure if it was this day or the next but part of our trek followed what the locals call the French road. It’s the old road to Muang Sing. On my map it’s still marked as a minor road. I think probably it was never more than a trail. It goes to Muang Sing and the old market. For a period under French colonial rule, that market, was the major outlet for Laos to export opium to China.

Only parts of the old road are still in use as a trail.The Chinese built the current road in the 1970s. I found an old Chinese shrine along the current road and wondered if it came from that time.

Chinese Shrine on the road to Muang Sing

I asked Ket about the relocation of hill tribes and he said it’s often the younger people who want to move. More opportunity. Along the road there is always the possibility of starting a business. I had noticed at Ban Donexai that the village had seemed more prosperous than many I’d seen. I can’t argue with the obvious truth that there are many more opportunities close to the road. The kids go to school and the distance to a doctor or medicine is much smaller. If it were me I too would want to live on the road

It’s easy for me to look at the Akha and think they are better off staying far off in the hills removed from all the headaches of modern society as I know them. It’s undeniable that as a modern westerner, I find the villages far from the road where most people still dress in traditional cloths, fascinating. What is harder, is to try to look at it from the perspective of the people themselves. I like the way there is almost no plastic trash to be seen. Yet I too prefer to wrap things in plastic bags instead of banana leaves. I hope that I will like the modernization of the Akha peoples because it has improved their lot in this world.

Ket had worked in the early development of health care in Muang Long district. He said the reaction of people to very simple malaria drugs was a nice thing to see. Here before it was a killer disease, and in two or three days it was cured. He also said hill tribe peoples seem to be cured by the drugs better than lowlanders. He had required many days on a quinine drip to get over his case. Perhaps drug resistant malaria.

I realize that it’s hard to understand a controversial program as an outsider. So many other factors are involved, opium eradication, drawing the hill tribes into the larger Lao society, I just have to assume that with so many people seemingly intent on doing good that all is for the best. It’s not like the hill tribe people move away and then some army general starts logging or anything.

The Lao government also has a very long history of good relations with the hill tribes. During the years when the government occupied just a small portion of Laos, the hill tribes were their majority population, they were the soldiers and farmers of the communist movement in Laos. The concept of Laos and Laotians being all the people of the nation was enshrined in the ideals of the earliest communists. To call someone a Lao person simply indicates what country they come from, not ethnicity. Lowland ethnic Lao are only half the population. Laos is a country with a mix of languages and peoples.

When we took a break in the early afternoon I threw down my ground cloth and closed my eyes. The next thing I knew Ket was prodding me awake. I was tired from a cold night. Ket didn’t care, time enough to sleep when we get to where we were going.

Ban Nammat Mai or Nammat New Town, was abandoned. They had moved ten months before. The town looked like it had been left years ago. A lot of the roofs and floors had been used as convenient firewood when moving. No need to collect wood in this town. Abandoned or not Ket still used Nammat Mai as a teaching tool, showing me the different symbols on the gates and what they were for and why the gate in the first place.

I’ve heard people remark before on the small, toy like, AK replicas attached to Akha gates. Makes sense when you realize many of the symbols on the gate are to keep bad spirits out and to scare them away. Using guns from the time they are children the Akha certainly recognise what an extremely deadly weapon the AK is.

Bird on Gate Mongla

There is also a crude fertility symbol by the gates. Simple tree branches with forks in the right places so that one could be considered female, and the other with the extra branch sticking out, male. They are placed in such a way as to be copulating. Many children makes a village prosperous. On the other side of town Kep remarked on a tree with lots of chopped marks from machetes, Kep said returning hunters would leave an ear from the carcass in the tree and fire off a shot to let the village know they were returning with meat. I suspect they only do this for large animals. Not many ears on a bird.

That night the hunters were shooting down at the spring a hundred and fifty meters away. In the morning some shots also just after sunrise in the direction that we had come from. Just so no one misunderstands the hunters not only hunt for meat, they hunt for cash. The price of wild meat in town is much greater than pig or beef. A hunter can take a civet in to town and return with cash or a larger amount of pork.

When I returned to Luang Namtha I saw a friend stepping out his back door with an animal to clean in a pan. The animal had already had it’s hair removed. It had large teeth and a long tail. I’d never seen one before, and although my friends English is excellent, he didn’t know the English name. I carefully wrote down the name, tam yien, and went up the street to the Green Discovery office. As I suspected it was a civet. I’d seen this same animal around in markets dried before. Drying out an animal is a good way to keep it until sale. No refrigeration most places.

I don’t eat wild animals in Laos as a general rule. I’m afraid that with such good hunters there is the possibility of having an adverse affect on animal populations. Also where do you draw the line, what about the tiger and owls, or hawks and falcons. Insects and fish I eat. This animal was already bought, and I accepted the invitation.

My friends wife was nursing as was my friends sister in law, so they didn’t join us. Local tradition has it that the meat from the civet is inappropriate for nursing women, and women in general I think. There were only guys at dinner. Preparation was done by chopping the yien into small pieces, bones and all. Then quick frying it in the bottom of a soup pot, then adding the other ingredients, and simmering for a long time. The only thing I tasted was Bai Kee Hoot I think we call it kafir leaf. I didn’t notice afterwards that I felt much more macho.

Getting back to the trekking part of this story….

The third day was warmer, it was the first day I began to feel the advent of the hot season. We crossed and re crossed the same small river many times. One time as we were walking along the top of a bank waiting for the next crossing I joked and suggested we use a large log that was spanning the stream. Others had used it infrequently, branches along the top were broken or bent and there were slight scuff marks on the bark. Ket said that at one time he had considered using it but the danger of a fall was just too great for him to take trekkers across.

The forest through the trees

It was during the rainy season when most of the old part of Luang Namtha had been flooded out. The drainage above this particular river is close by. There had been one of those cloud bursts where a lot of rain comes down in a very short time, and all of the regular wet season crossings were washed out or covered over. This particular log lies a good twenty feet above the river. Much too far to fall. Easy enough for hill tribes people if they are careful, potentially catastrophic for eight tired wet trekkers.

Eventually Ket made a new crossing further downstream using a new piece of bamboo, then lashing a second to the first for stability, then a third above it for a handrail. A foreigner almost fell off anyway. Later there is another crossing that has to be made and can’t be avoided. By then it was dark. Kep got around it by making a new trail, he had to cut the thick underbrush with his machete and left the trekkers with his assistant. After cutting for a ways he would return to the group and help them to walk further, then repeat the whole process. Can you imagine in the almost pitch darkness of the jungle, rain clouds obscuring what light there is from moon or stars. Ket doesn’t tell stories using adjectives, it was very easy to imagine anyway.

When Ket called the office for assistance on his cell phone the tuk tuk, couldn’t get through because of the road being washed out. I’ve forgotten what time Ket said they got back to the office from that trek.

At one place while walking close to the river Ket pointed to a stick. I didn’t get it. Ket grabbed the wire attached to the stick. Still didn’t get it, “look” he said, “hair”, “trap”, the light went on upstairs. I’d made the same kinds of traps as a kid until my grandfather told me they were against the law. You bend over a sapling and tie a string to it with a looped slip knot at the end. You set the trap by barely securing the string to the ground with a peg or any other way. The animal wanders through, bumps the string and then is jerked in the air and dies. In this case the civet bit through the bit of electric cord that had been used as a string. He’d left some neck hair where the tight cord had been strangling him. Ket said that’s one civet that will never get caught in that kind of trap again. Good grief, I’d imagine.

Sapling that was almost all she wrote for some civet

That’s how the trek went, over and over again. Lots of birds. At one point when Ket pointed out a big bird and asked if it was an eagle. I don’t know. What’s an eagle? If I get close enough I can tell a golden, or an immature bald eagle, but in Asia? Big enough, and the feathers were splayed towards the back of the wing the way they do. Well I know it wasn’t a vulture. Looked to be the size of an osprey. You would need a video camera and a tape recorder just to get down half the stuff Ket comes up with. Then you would have to write it all down to make sure you had it figured out.

Bill the guy who helped found the Boat Landing, and handles advertising for Green Discovery, spent years with Ket doing health care and then the trekking development. Kind of makes you wonder how much Bill knows about all these things. People say not only does he speak Lao like a Khaysone monument come to life, but knows the regional dialects too. Talks to himself in Thai Lu when he spends too much time alone, and can speak a whole lot of Akha, must be a reincarnated witch doctor.

Soon on the last day we entered the area cut by the villagers of the new Nammat Mai. I don’t know the name of the new town they built, I suppose I could call it Nammat Mai Mai. New new Nammat.

We started walking through recently burnt trees from old growth. This was something I hadn’t seen much of before. Lots of work growing rice between the tree stumps. A lot of the trees were being cut for wood. The people cutting the trees were Khamu. Cutting beams and planks from trees using a hand powered rip saw is a lot of work and takes time to learn. The Akha were paying the Khamu to do it.

I was very curious as to costs, amount of time, and species of wood. At one point the Naiban of the new village came walking through the working men and complained about the pace of work. He needed this wood to build the new town. The wood cutting was contracted on a piece work basis.

Eventually we made our way into the new town to be surrounded by children and grannies begging with bracelets. Tourism had made it’s way here before us. I kept pointing at Ket when his back was turned but the kids were having none of it. They knew he wasn’t buying any. I looked around and this place was low on my pants scale of children. I size up poverty by seeing how many kids are wearing pants at what age. By the time kids are two and a half or three they too like to cover themselves. Here a lot of the boys of eight and nine only had underwear, and some kids not much younger had nothing. Putting the best face on things I said to Ket well at least there are no big bellies from malnutrition. At that Ket started to mention which kids had the tell tale bellies just the way he pointed out animal signs. The difference was he didn’t point or look directly so no one could tell that’s what he was doing. I wonder how many other times I just didn’t see malnutrition.

The temptation in these situations is to just give money. They are so poor and it is such a small amount. Well we know that doesn’t work. Just turns kids into beggars. I could have given money to the Naiban I suppose, but it would have been a drop in the bucket. I wonder what it costs to feed a village like that for a day, or a year? How much for health care? They were waiting for the depths of the dry season to decide on running the pipe from the spring that was a half a kilometre away. Wanted to see if the water still flowed when the year was at it’s driest. I asked Ket if he thought the people boiled the river water before drinking. Mostly he said. And the ones who don’t? They drink from the river.

I realize the first year after a village moves has to be the worst. Gardens not yet planted, rice fields to be cleared, houses only bamboo shacks built on the dirt. I know the old folks and kids die, it’s inevitable. Yet they move of their own free will, I guess like all they want a better life.

From the Akha village we walked down the road further, past the established villages of the lowlanders. Not ethnic Lowland Lao and not hill tribes of the high mountains, you have to look carefully to know that they are Thai Dam, Lanten or Thai Daeng, and further on and in town, Thai Lu. It was reassuring to see once again little children dressed and clean, the pride of their mother’s eyes. It was Sunday, lots of music and eating food.

When we came to the crossroads near the stupa Ket called for our ride. I suggested we stop in the small restaurant for a soda. Actually it was a board with some soft drinks on it so that you could tell here were drinks for sale. I had been here just before the trek when I came to look at the stupa. I even remembered the owners name, Bang. Ket was surprised that we already knew each other and Bang was surprised to see me come walking out of the mountains with a local guy.

They talked for a while and then Ket asked me if I’d been in the war. I laughed and told them that luckily I’d been too young. At fifty, for Lao people, I wasn’t too young. The Americans closed up shop quite a while before the war was over for the Lao. When I graduated from high school in 1974 the draft had ended, for the Lao who often joined the army at 15, and for whom the war lasted another two years after that, I was old enough.

When I’d met Bang before, I’d of course asked about the stupa and the old part of town. I just wanted to know if I should feel collective guilt or anything. Turns out the town was flattened by the Lao Air Force. I was off the hook. Through another tourist’s girlfriend, who was Thai Isaan, and therefore spoke Lao. I, and the couple, asked Bang lots of questions about the period. He said they had to move away because the bombing was so intense, and the Lao government had helped the whole town to rebuild after the war.

Toppled Tat The bombed stupa above Luang Namtha Old Town.

When Ket and I parted at the Green Discovery Office I hand shook him, and slipped him a big tip, I’ll bet he forgets me a lot sooner than I forget him.

Luang Namtha

Tatu and His Handlers

This is an extremely nice Spanish couple I met in Luang Namtha. I saw them at the restaurant next door to the internet place and when they left I rushed up the street to ask them for a photo. I thought them very photogenic. They also signified to me the coming of age of Luang Namtha, the town is now a destination in itself with quite a few guest houses and people coming to stay for a week or even more. The peace sign isn’t posed, I didn’t ask him to do that.

The little dogs name is Tatu. Tatu also comes from Spain. They brought him on the airplane without a problem. The only difficulties they encountered were at hotels in Thailand. Being somewhat tuned in to the culture here I can only imagine. Try to bring a dog in our house and my wife would hit the roof, wouldn’t even allow it in the soup pot.

I wrote down these people's names but lost my notebook. Like more than a couple young “hippies” I met on my travels they were very friendly and down to earth. I think people just stereotype too often. They never used “man” as slang once.

There are two things to note in the picture. Above them in the background is the sign at the entrance to Zuelas Guest House, and both of these young folks are wearing a Tong, as in the man purse I posted about. Cool.

Luang Namtha Airport 2/07

This other picture is of the airport. More than anything else the airport will open up Luang Namtha and it’s environs to the casual tourist. If people can fly, they will come. Only the most daring of tourists will take an hour or two bus ride, anyone will fly. As of today to get to Luang Namtha you can either take a 5 hour from Luang Prabang bus to Udomxai then bus to Luang Namtha. Fly to Udomxai then bus. Fly to Huay Xai over on the Thai border then a five hour minimum very dusty in dry season maybe a lot longer and muddy in wet season bus ride. Bus ride down from Boten on the China border. Or even more unlikely from Huay Xai fast boat Xiengkok, then Sawngthaews to Muang Sing and Luang Namtha. There is no easy way.

Today I estimate there are at least fifty tourists a day in Luang Namtha. A lot more than you see on the street. A lot of people don’t even stay on the street, but in some of the guest houses over towards the bus station. Three years ago Luang Namtha was more a place to stop on the way to Muang Sing, very few used it as a destination in itself. I met people in Luang Namtha for whom this was it, their most off the beaten track destination. I’d guess the tourist visits have doubled since three years ago.

The airport as well as the new banked hard surface road are going to be done someday. It seems as if that day will never come to look at things. Such big projects such teeny machines. They are working at them both. Work goes on seven days a week, and they are using a lot of heavy equipment. I saw the only bottom load dumps I‘ve seen in Laos on the road. When they are done watch out, Luang Namtha would be a different place with another hundred and fifty visits per day.

Zuela

OK here we go, my first blatant plug of a business.

A few years ago while in Muang Sing I met a guy Vong who worked at the bank. His English was very good and it turned out I had rented a motorcycle from his business over in Luang Namtha.

That night he took me to a guest house opening party. The guest house was owned by a local oficial. While there, through him as a translator, someone asked my why bother coming to Muang Sing or even Laos it being such a rural out of the way place. I replied (speaking in my limited Lao) how the Lao food was so good, I waved my hand at the view we could all see out the front of the restaurant, the sun was setting over fields of rice all the way to the mountains, and said how beautiful the countryside was, and I mentioned the easy going manner of the Lao people. Actually the normal type of thing you say to anyone when they ask about their own country. The lao lao had already been flowing, and they loved my praise of Loas, hard to go wrong praising a country to it's inhabitants.

When I went back to Luang Namtha this year with photos of Vong and Sai’s young daughter he was standing in front of his brand new guest house. Good connections to be had at the bank? I stayed there that night and a few more nights when I went back up to Luang Namtha province.

Here are the details as of this writing.

All rooms are $6 except the two rooms available out by the kitchen that have a shared bath and are $2. All rooms have hot water but as of now no AC. They are large, clean, have a place to hang clothes, wooden furniture, a painting, ceiling fan etc, There is a lot of wood used in the construction. Most of the walls are brick painted with some kind of sealant to make them shiny and clean, similar to the outside of the guest house.

The restaurant has an extensive menu kind of in the style of large western orientated hotels in Vientiane. (What that means is that if you are expecting something to be like back home fugetaboutit. But it will be very palatable by western standards, look back at my post about Yam Moon Sen three posts ago. Made not very hot, and not too spicy just for you) If you are looking for regular Lao food order from that portion of the menu. Coffee comes in coffee mugs and the restaurant area is a quiet pleasant place to while away time reading or writing post cards.

The entire guest house itself is fairly quiet being set back off the street down as small short alley. The way to find it other than asking or looking for the small sign is to look for the tallest thing on “the street”. That’s the brand new four story tall guest house that was being built by their neighbours next door. Highest building I saw in Luang Namtha.

When I urged Sai, that’s Vong’s wife, to up the rates so to make them comparable to similar rooms in the area she replied that she was more interested in having a full house every night than making tons off one room. They do seem to fill often. Mostly word of mouth but also the mini bus drivers like to take the guided tourists there. The standards meet the requirements of the guided tours and they save ten or fifteen bucks. There is no pressure to eat in the restaurant, rent a motorcycle, change money, or use any of the other services they offer. They are happy that you stay with them.

The hotel is run by Sai, the motorcycle rental by her mom, bikes are serviced by Vong’s brothers, and there are many brothers and sisters working throughout.

The name Zuela comes from Vong and Sai’s little girl who is now of an age to pretend to have tea parties with her friends and is cute as a button.

My Man Purse

Murse: A purse made for males.

While waiting to catch a bus out of the Luang Namtha dirt parking lot cum bus station I saw a guy with a bag like this. He was dressed entirely in hill tribe clothes so I assumed he didn’t come from a town on the road. It seems as if men who come from close to the road don't wear traditional clothes. His were hand woven, black, slight bits of coloured embroidery, the whole nine yards, all in a very new and clean state.

What made him stand out for me was that even though Luang Namtha bus station is pretty much on the map with a direct to Vientiane and a lot of foreign tourists in town, this guy wasn’t acting like the shy guy from the countryside. He was pretty broad shouldered and had a lot of muscle. His wife was strong too. They were negotiating the rate for some cartons or bags to somewhere by the back of the Sawngthaews, and unconcerned with the people around them. Pretty self assured for country folk.

I noticed the tong the guy was carrying, it looked a lot like the one in this picture. A tong is that over the shoulder bag that a lot of people carry around in Laos. They have been adopted as a good carry on the bus and around town bag by a lot of westerners, particularly the fisherman pant, rasta, full moon party, crowd. When I walked in the woods with a Hmong local guide I noticed how easily he shifted it’s weight while ducking through the thick brush. I wanted one, I thought they looked totally cool.

I hadn’t really warmed to a style until I saw the one in Luang Namtha. I liked the way the woven pattern went closer together towards the top and then became strings using the same pieces of thread. Partway up the strap where mine has one piece of coloured thread the one I saw at the bus station had a couple of tassels and a small piece of silver.

When I got to Muang Long I asked Tdooee the director of tourism what hill tribe made this type of tong and where could I get one. He laughed and said Akha and that I could get one during my trek. I’ve seen a lot of Akha of late and I was surprised I hadn’t noticed the tong before.

The trek was a little fast for discussing and buying tongs but I kept my eyes open and sure enough I started to see them hung on walls and even carried by people. I didn’t see any that even remotely matched the workmanship I’d seen in Namtha.

I had severe reservations about trying to buy someone’s tong also. It didn’t feel right. Once in Muang Long market a few months ago I watched a mini van tourist, (that’s the kind that blows in with a tour guide and minivan) stop at the market, long lens the hill tribe women selling vegetables, then have the guide negotiate a price for a basket a young girl was selling her greens out of. The transaction was over in ten seconds and the girl was left to search for a plastic bag to carry her stuff off with. The whole scene left me wondering about the righteousness of buying handicrafts that someone was using as personal items, especially since I’d done something similar to a kid in a computer gaming store in China.

At the government crafts cooperative in Muang Long I did buy a tong that was Lanten. There weren’t any Akha ones. Back in Vientiane I dropped by the cooperative across the street from the morning market right next to the post office. Free parking he he.

Sure enough there were some pretty nice Akha tongs. I asked the Hmong lady that owned the stand what kind of people made the tong, she replied Lao people. True enough I guess. When I told her Akha she was happy enough to know and thanked me for telling her, she can use it as an informative selling tool. She had stuff from many peoples in the shop. Yao women’s shirts with the fuzzy collars, lots of Hmong stuff, all kinds of things.

There is a specialty industry in making Hmong style dress up cloths for particularly overseas Hmong from America.

I was concerned after I bought the tong that it had been made of fishing line. Tdooee told me sometimes they are. Makes sense, nice strong string, but I was hoping for something a little more green as in natural. Low and behold my wife informs me the string is made from the bark of a small tree. How she knows I don’t know.

The man purse label I read in a story by a guy who traveled into Sayabuli province. The name is great because it seems to poke fun at guys who carry them without being homophobic. Well I’m one now. I wore it to the market yesterday and liked it. I can see where everything is inside it. Of course so can everyone else but the strap is so short it hangs just below my armpit, and the weight of things hold it closed.

In the Lao alphabet they have certain words that remind people of the letter. Kind of like our “A is for Apple”. In this case it’s Taw-Tong for the T sound. Forever enshrined in Loa language.