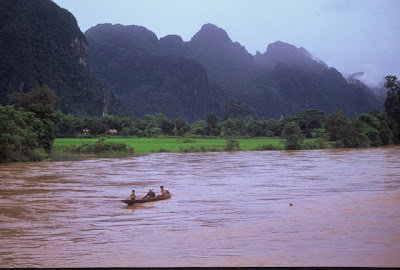

above, Vang Vien Before Tourism

Before I do a cut and paste from The New Statesman I'll give some background.

Joe Cummings had a lot to do with my initial view of Thailand and Asia. He was the author of the Thailand edition of the Lonely Planet book when I first went there and his attitude and outlook made a lot of sense to me then, still does now.

Joe encouraged readers to dig a little deaper, look a little closer. Learn some words, eats some local food, talk to some people. Eventualy I lived in other countries, but I always used his template of learning about the people of the country as a guide.

Joe's books were exaustive and also up to date. His insight into the language, the people and culture gave him a perspecive unmatched by todays writers. After all how many guidebook writers can speak in the language of the country they write about, how many live there? More likely they are young, paid for a brief few week mad dash around the place collecting prices and names of hotels, and then it might well be off to the next country half way around the world.

Without further ranting here it is.

Beauty at a price

Joe Cummings

Published 17 July 2008

Concrete hotels, go-go bars and drug tourism have scarred Thailand, Laos and Cambodia - yet it is not too late to develop a less destructive travel industry. Part of the New Stateman's special focus on South East Asia

Tourism in mainland south-east Asia has entered a new era. Thailand, once something of an underground destination, has become hugely popular, attracting more than 12 million tourists every year. Its top resorts, such as Phuket and Koh Samui, are swamped by foreigners, particularly in the winter high season.

But political and social trends are reshaping the country's travel scene. The stereotype of Bangkok as a city that never sleeps was shattered by a "new social order", propagated by the conservative Thai Rak Thai political party (reformulated after an anti-TRT coup as the People's Power Party). Prompted by the then prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra's conviction that "dark influences" cause all manner of social ills after midnight, the Thai government began imposing early closing (between midnight and 2am) on bars, discos, massage parlours and every other entertainment venue.

Nowadays, tourists arriving in Bangkok expecting to party all night often say they feel cheated. "If I wanted to head home early when the pubs shut," I heard a young Englishman complain recently, "I'd have stayed in Brighton."

Although Thaksin himself turned out to be something of a dark influence (the state has filed or is considering more than 20 charges of corruption against the former premier, who was deposed in a military coup in September 2006), the new social order's strict closing times have remained in effect.

The city's notorious go-go bars along the neon-splashed lanes of Patpong, Soi Cowboy and Nana Plaza have been heavily affected by the policy. Their clientele was used to arriving around 11pm and staying until 3am or 4am, and even now the clubs remain relatively empty before 11pm. The owners and their female staff - many of whom depend on after-hours "dates" arranged while at work - now have to solicit business over the course of just three hours.

But in neighbouring Cambodia, Phnom Penh, once considered one of the region's more conservative capitals, is being touted as the "new Bangkok". Two of the city's most popular, long-established bars, Sharky's and Walkabout, now open 24 hours a day. Others won't close until the last customer leaves. Trendy bars and cafes, full of twenty- and thirtysomething businesspeople and tourists, have sprung up along Sisowath Quay, supplanting classic post-Khmer Rouge drinking holes such as the famous Foreign Correspondents Club.

Similarly, Siem Reap - not so long ago a dusty outpost humbly prostrated at the feet of the magnificent Angkor Wat temple complex - has recently been transformed into a city of art galleries, gelaterias and chic, architect-designed hotels such as the Hôtel de la Paix. The city has become such a destination in its own right that it's not unusual to meet a foreigner with no plans to visit the Angkor complex nearby.

The heady scent of marijuana, readily available for US$1 per neatly rolled, Bob Marley-sized spliff, wafts down the streets of both Phnom Penh and Siem Reap. No one in Bangkok - a target of Thaksin's deadly drug wars in 2004, during which more than 2,000 petty dealers were extrajudicially executed - would dare smoke cannabis in public. In tourist Cambodia, however, it is relatively commonplace.

The right kind of travel

Drug tourism also flourishes in neighbouring Laos, particularly in Vang Vieng, a small town wedged in a river valley lined by limestone cliffs. Dozens of limestone caves, many of them holy to the Lao people, are Vang Vieng's main daytime attraction, but when night falls, foreigners often drift towards the town's half-dozen opium dens. I asked one den owner about the intricate wood-and-bamboo pipes on display. "Those are for tourists," he replied. "The locals prefer these," - smaller glass pipes filled with ya baa, the crude, locally made amphetamine. "Much stronger."

But some tourism in other areas is more carefully managed. Si Phan Don is a cluster of impossibly scenic islands in the middle of the Mekong in southern Laos, close to the northern Cambodian border. Here, where the Mekong reaches its widest extent, a handful of islands are inhabited year-round. Peaceful and palm-fringed, they look like a mini-Polynesia.

Two of the islands - Don Det and Don Khon - are lined with guest-houses, constructed simply, in local styles. River breezes take the place of air-conditioning, and the islands' power generators are typically engaged from 6pm-10pm only. The main tourist activity is boating from island to island to observe Lao village life. Villagers also offer boat excursions to see one of the last surviving pods of Irrawaddy dolphins, found only in mainland south-east Asia. It is unknown how many are left in the area - perhaps as few as 20 - but the Lao provincial and district governments work hard to protect them from local fishermen, providing free dolphin-friendly nets in place of the deadly gill nets they used until recently.

Similarly, local people in the northern Lao province of Luang Namtha have, under their own initiative, created village-based eco-trekking programmes in and around the Nam Ha National Protected Area. Extending to the border with China and contiguous with Yunnan's Shiang Yong Protected Area, Nam Ha is one of the most important international wildlife corridors in the region. It is also home to minority hill-tribe groups, including the Lao Huay, the Akhas and the Khamus.

The hill-tribes supply and train leaders for the small group treks in tribal lands, which are scheduled so that no village or area is repeatedly inundated by tourists. The programme has been so successful that the United Nations Development Programme has recognised it as a "best practice" poverty alleviation intervention, and it earned a United Nations Development Award in 2001.

In many ways the late-blooming tourism industries in Laos and Cambodia, delayed by decades of war, have benefited from observing the mistakes Thailand made during its 1980s and 1990s economic boom. On Thailand's vast Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand coastlines, which still attract by far the majority of tourist visitors to the country, the negative impacts of overbuilding and congestion in parts of Koh Samui and Phuket have served as vivid lessons on how not to develop natural attractions.

The December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which devastated small portions of Thailand's Andaman coast and took more than 8,000 lives (roughly half of whom were foreign tourists), brought beach tourism to a virtual standstill for a full year afterwards. A few Thais argued that the tragedy offered the opportunity for lower-impact rehabilitation of the affected areas. However, most business owners simply created the same tourism landscape as before - which has, at least, helped Thais avoid the harmful aspects of extinct local practices such as tin mining and cyanide fishing.

Thailand, Laos and Cambodia are all increasingly struggling to identify and attract a market that lends itself to sustainable tourism. One of the latest buzz terms used by national tourism offices (NTOs) in the region is "high-yield traveller". On the face of it, the concept seems relatively clear: "We want visitors who leave behind a lot of money." But who are the real high-yield travellers? Unfortunately, most south-east Asian NTOs define them as the visitors with the highest expenditure per day. The NTOs believe their task is simple: target the richest and most spendthrift.

Yet per-day expenditures are not the whole story. Higher-spending tourists typically demand hotels packed with imported amenities and foods, and managed by foreigners or local people trained overseas. Tourism revenue leaves the country through the purchase of imported goods, through expatriated salaries and through overseas tuition. Most of the high-expenditure-per-day figures are eroded by such hidden costs to the host country.

Budget is better

Other hidden costs of the higher-spending tourist are environmental and cultural. The typical international hotel chain may offer a nod to local architecture, but neglects ways of cooling living spaces that do not involve using air-conditioning, for example. Local people, awed by the hotel monoliths, may gradually come to look down upon their own ways of building, thereby contributing to a loss of culture.

Meanwhile, the average backpacker or budget traveller - a sector of the market increasingly spurned by NTOs - stays at local-standard hotels and guest-houses, eats at local restaurants and buys local handicrafts direct from village crafts people. The income "leakage" is much less, and because the backpacker typically stays in the host destination longer, the net income is in fact usually greater than for the high-expenditure-per-day traveller.

For the moment, tourism in Cambodia and Laos seems aimed squarely - whether intentionally or not - at this high-yield, low-impact market. Thailand attracts a mix of mass-market, luxury and budget travellers; it cannot turn back the clock to a time when it was at the same level of development as Cambodia or Laos. However, it is not too late to adjust Thailand's tourism marketing policy and to work towards preserving the increasingly fragile cultures and environments in the country's less explored areas of the north and north-east.

The downturn in the global economy, and the resulting dip in south-east Asian tourism, provide another chance for the industry to reflect on its way of working, another opportunity to decide whether the region needs more multinational-dominated mega-resorts - or a more old-fashioned, local approach to welcoming visitors.

Joe Cummings, an author of Lonely Planet's Thailand guide for 25 years, has spent most of his adult life in south-east Asia